Your Search Engine Sucks: Control, Profit, and Information Retrieval

Incredible - it’s been a year since I’ve posted a substantive piece here, and over six months since I’ve posted anything at all. It’s almost like I’ve been, well, writing a dissertation while applying for jobs! Well, the good news is that the dissertation is written (to be defended next week), and I’ve got a spectacular Visiting Assistant Professor position lined up at Temple University this fall. Back to blogging and writing music reviews.

I’m beginning to think of research plans to commence following the conclusion of my PhD work and publication of all my backlogged ideas (the dissertation has been rather like that clump of hair in your bathroom sink drain, that, once removed, allows the gushing of ideas - I mean water - to flow). One of my most promising ideas involves extendingof some of Bernard Stiegler’s philosophy into critical scholarship on geographic technologies. I think Stiegler provides a number of crucial conceptual challenges to geoweb and critical GIS bodies of literature that I hope to expand over the next couple years (or few publications, whichever burns me out quicker). Since I’m in the early stages of these ideas, the first step is to see, of course, how other geographers have written about his thought, and to see where they’ve written it. So I do a little bit of what we call in academia: “digging”. That is, I consult the Googles.

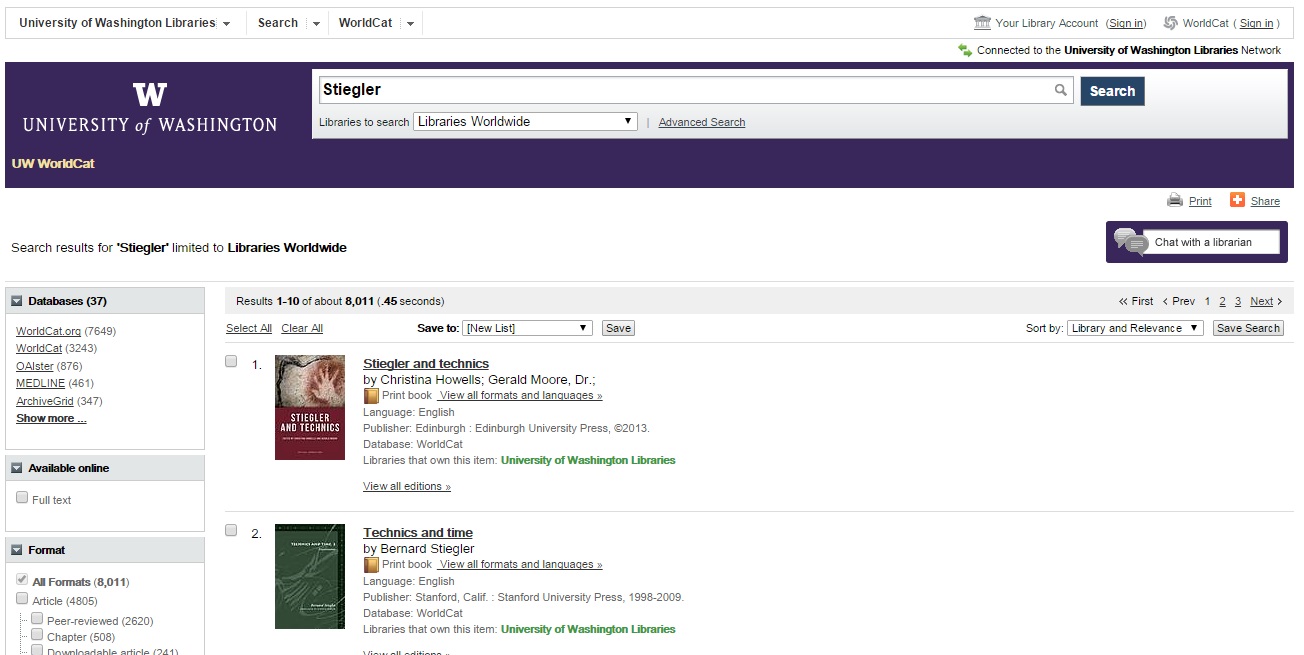

Actually, I did what they trained me to do as an undergraduate, and what UW Libraries instructs new geography grad students to do: I used the UW Libraries system to search for “Stiegler”. Hold off your (quite right) judgment that even to search UW Library’s system you must have a UW-specific login, which is only accessible to current students and faculty (hold on to that idea, though, as it comes into play later). Hold off that ideological critique, and notice that this search returns over 8,000 results.

Clearly I can’t go through this list to weed out useful sources. So, typically, I would limit these results either through (1) filter these results to make sure they only return useful results, like, those in English, or (2) specifying more information in the search, such as journals or authors. I can quickly narrow the results using approach #1: by checking the “Peer-reviewed article” checkbox, results drop precipitously to 2.6k, and below 2k when I check “English” (my guess is that the other 700 are mostly in French, the language in which Stiegler usually writes). In the list of authors, I’m unable to check all but Stiegler, which would be useful since I want to read others’ interpretations of his work, not the primary sources. Since 2k is still too many to be time-effective, I engage strategy #2, by putting “Bernard” in front of Stiegler, and checking the same boxes. I’m now left with 213, and they come from all across the academy: philosophy, media studies, science and technology studies, anthropology… More useful, but identifying the geography-specific articles is daunting.

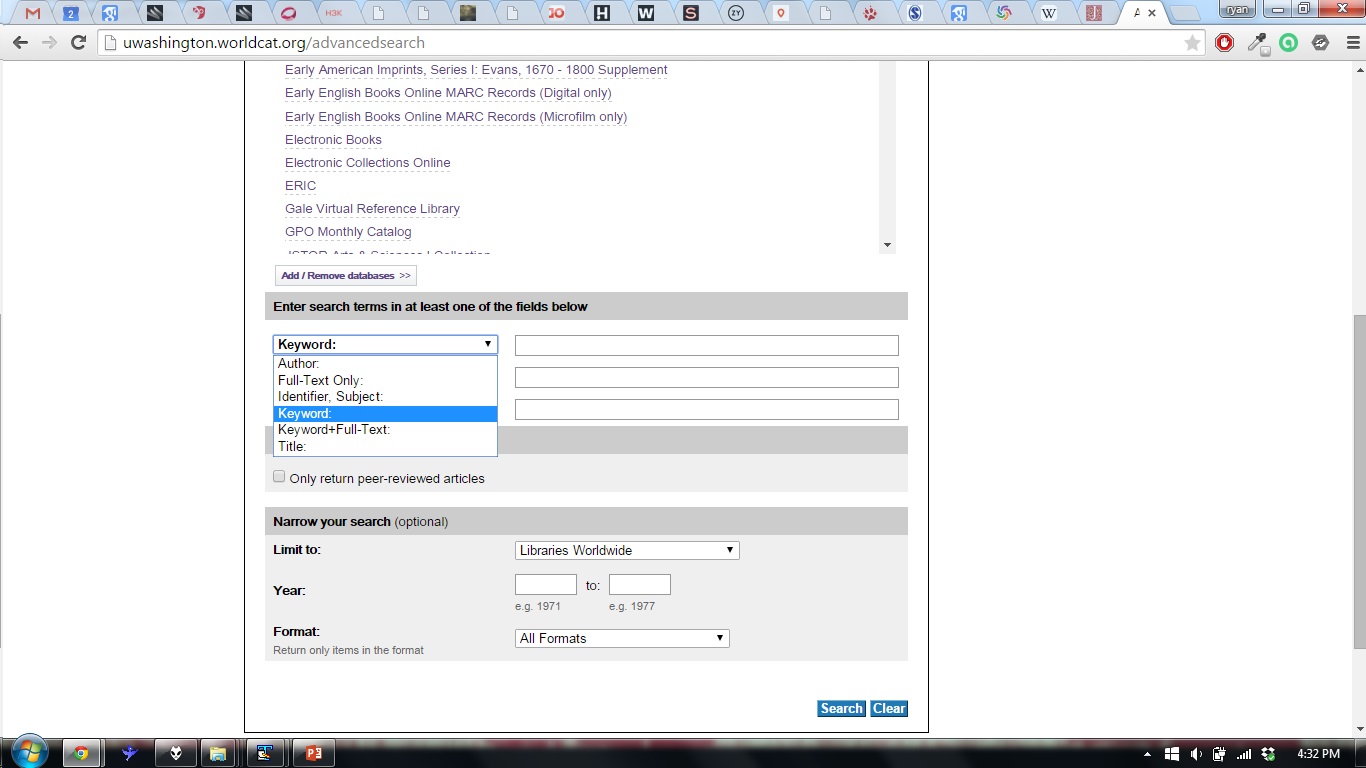

My next thought is to target my search toward specific journals. Turns out UW Libraries search - even the advanced search - doesn’t allow you to enter the journal name. Not cool at all. Ugh. Off to individual journals’ websites to search there.

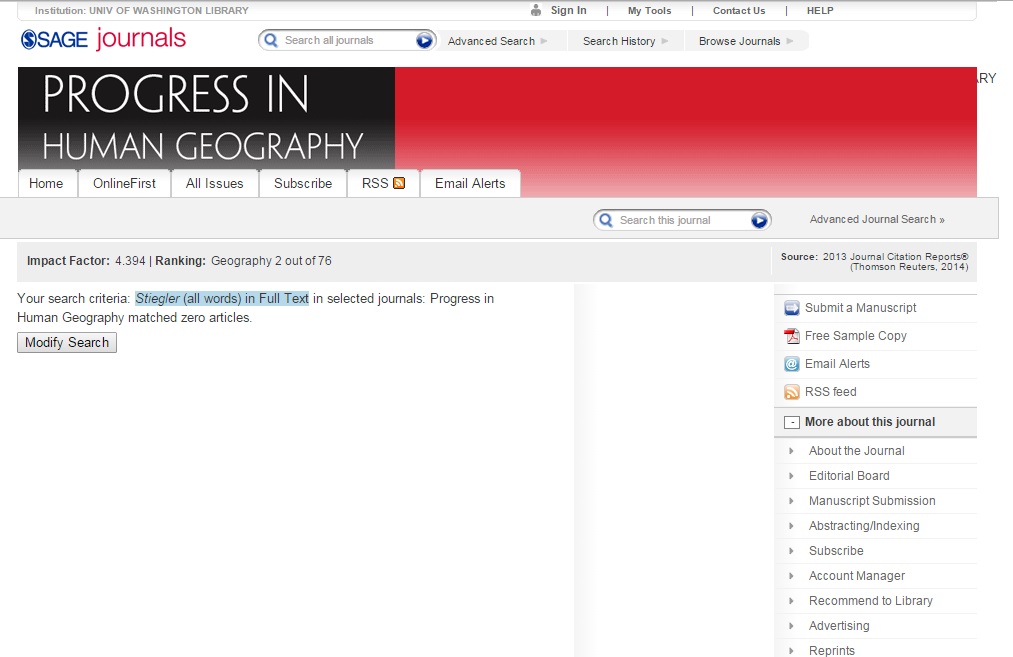

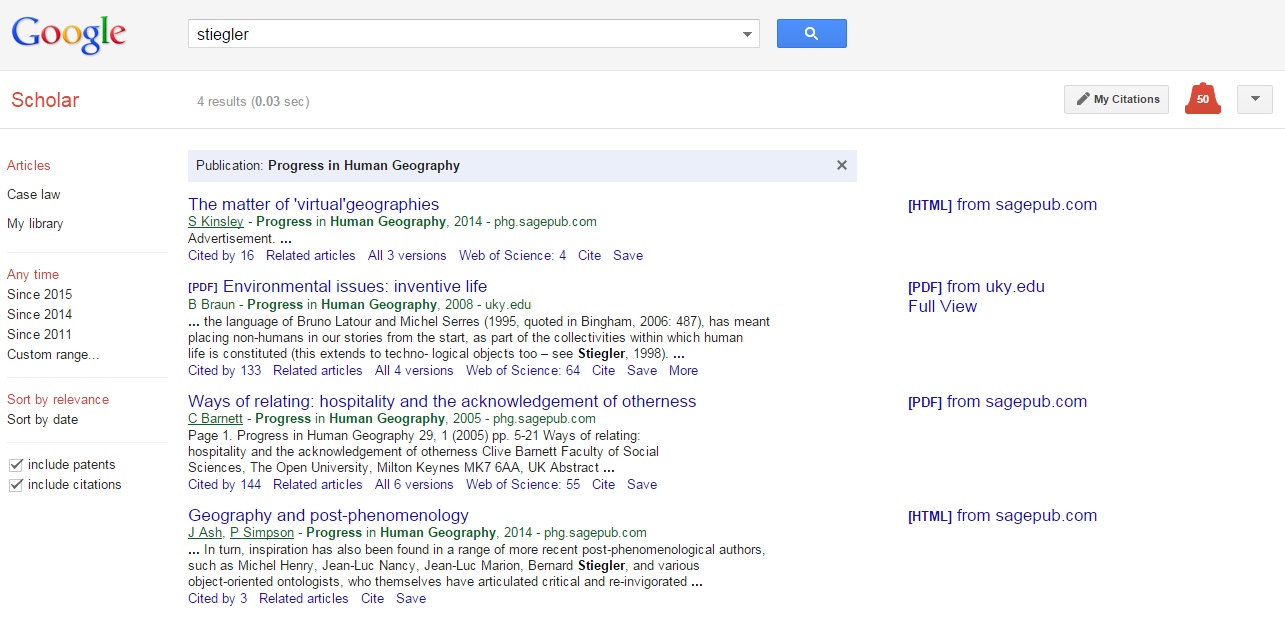

So I go to one of the top-ranked journals in geography, Progress in Human Geography, which would be a good home for the particular article I’m envisioning. It’s either good news or bad news, depending on your perspective: zero articles are returned, which could mean I’m exploring new territory - or it could mean this is the wrong journal for writing about Technics and Time. Let me check other journals.

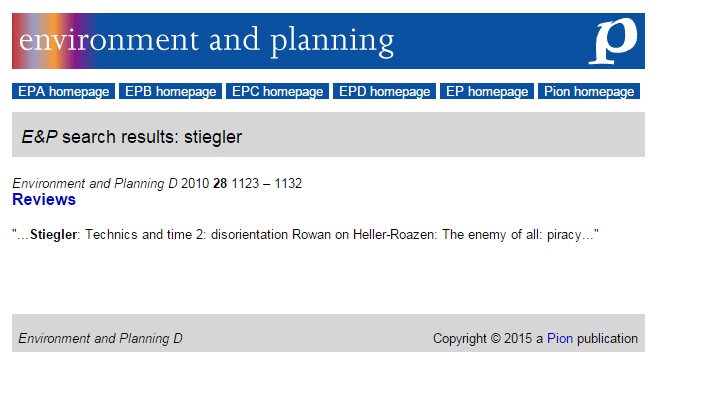

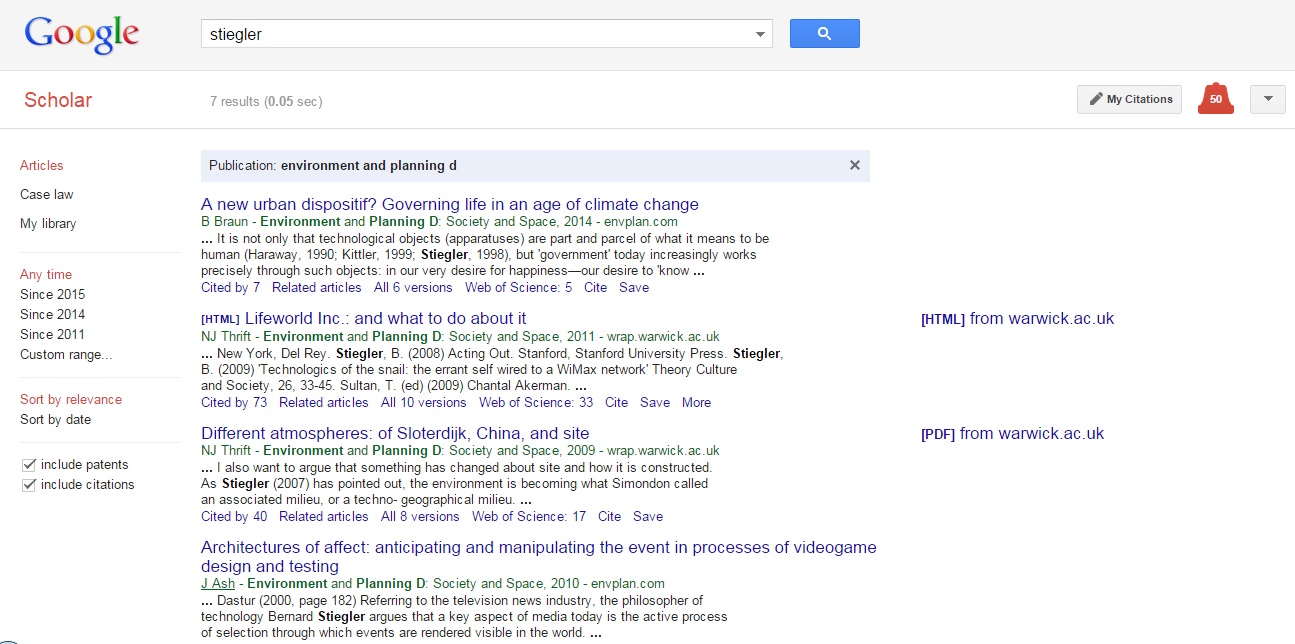

Another highly-ranked journal suitable for this nebulous quote-unquote article, Environment and Planning D, returns only one result when I search their site. And it’s a lousy book review (the review’s content isn’t lousy, but the fact that it’s a review and not a substantive engagement is what’s lousy).

And so on and so on, across the highest-ranked journals in our discipline. Same story at most of them.

By now, dear reader, if you are an academic or for some other strange reason highly familiar with conducting literature reviews in 2015, you’re probably shouting various other sources of information at the computer screen. The elephant in the room is the one I already mentioned but swiftly dropped: Google Scholar. The first major difference you notice when doing an advanced search here is that you can enter a journal name to search for articles in a particlar publication. The second, less obvious difference, is that you can remove authors from the list of results. So, if I do a general search for “Stiegler”, I can remove articles written by himself; I can also remove authors who typically write in very different subdisciplines than my own, making results more applicable to my research.

But the best difference? FFS, it returns more results for each journal than the journals’ websites themselves. I won’t even bother comparing it to UW Library’s search results, other than to say that they’re exponentially more useful. Here are the results for Progress:

And for EP-D:

Now, by intention here is not to advocate for Google Scholar - other than to point out to other researchers that their results are better - and far less to disparage UW Libraries and the services they provide. My experience at other institutions suggests this is a far broader problem than just UW. My point, rather, is twofold: one, academics have got to get their, um, stuff together when it comes to information search and retrieval. When a private company so blatantly and embarrassingly reveals academic search engines’ weaknesses, something needs to change quickly. If there’s a reason to continue using alternative search engines, I would be open to hearing them, but I have my doubts. A simple search for “Stiegler” at UW’s Library site searches 37 databases, not one of which I need to be aware of (particularly since the discipline of geography is not-so-shockingly underrepresented in this list of databases). Adding more seems counter-productive and resource-inefficient. Relatedly, libraries need to acknowledge to students that their databases are the best sources of scholarly knowledge retrieval: it doesn’t do students any favors.

Second, and most importantly, the academy writ large needs to have a deeper sustained conversation about the relations between knowledge access, profiteering, and proprietary control over information. At stake is no less than the 21st century model of scholarship itself. The university has reached a sad day of impending privatization when the for-profit corporation provides better access to locked-down academic research than the databases and software designed expressly for that purpose – by the very companies who lock it down. This is a double-edged sword: companies lock knowledge and scholarship behind paywalls, and then provide shitty – excuse me, “inexcusably bad” – access to that very knowledge. To be sure, this is a conversation that ebbs and flows, with the issue of open-access journals playing a prominent role. Especially pernicious are the times when the companies benefiting from closed-access research - I’m looking at you right now, Elsevier - engage in outrageously problematic activities, such as, I don’t know, arms trade fairs. There are many complex issues in play here, including “digital libraries” such as JSTOR to which academic libraries subscribe for indexing purposes, for-profit publishing houses that dispossess authors from their intellectual property, and shrinking university budgets due to the increasing privatization of the university. And there’s a fantastically complex tapestry of tools and services that play into academic knowledge retrieval - nod to the Web of Science. However, these are all intermingled rather than separate issues, and its complexity should not foreclose critical, reflexive conversation.

And again, in closing, this is not a naive endorsement of Google Scholar, although there are some practical reasons to use it before this whole mess gets sorted out by scholar-activists and the politically-minded.